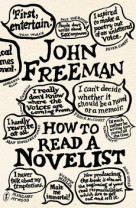

John Freeman has my dream job. As editor in chief of the well-regarded UK literary journal, Granta, he interviews seminal writers the world over about the nature of their work and their ideas.

How to Read a Novelist, ipso facto, is a dream of a book.

It’s a well-produced compendium of fine pieces about literary luminaries as diverse as Marilynne Robinson, Philip Roth, Siri Hustevdt, Doris Lessing, Kirin Desai, David Foster Wallace, Toni Morrison, Kazuo Ishiguro, Geoff Dyer and Peter Carey — pure gold for a bibliophile like me.

Freeman’s introduction got my motor running. It explains how, while living in his first New York apartment in a Brooklyn brownstone, a bookish couple fuelled his love of literature and, more specifically, a John Updike mania.

Freeman later comes to understand that he had been “tracing” his life over that of another writer and interviews with Updike prove revelatory in that respect.

During one such interview, Freeman told Updike that he had been in Maine finalising his divorce.

Subsequently, the publicist told Freeman that Updike was reticent to be interviewed by him ever again because he had revealed too much of his own personal detail.

“If I hadn’t known it before, I knew now,” writes Freeman, “it was a breach of everyone’s privacy when a reader turns to a writer, or a writer’s books, for vicariously learned solutions to his own life’s problems. This is the fallacy behind every interview or biographical sketch, to tether a writer’s life too literally to his work, or to insist that a novel function as a substitute for actually living through the mistakes a person must live through in order to learn how to properly, maybe even happily, survive.”

In need of solace (if not a substitute life) I immersed myself eagerly in these interviews and profiles, cup of tea in hand, as if sitting down to enjoy the armchair philosophising of 55 good — and incredibly smart — friends.

All 55 (56 if you count Freeman who is, himself, a successful author and poet) were engaging enough to hear out to their conclusion — and to distract me from my own problems. I refilled the teacup many times over while I savoured their thoughts.

Marilynne Robinson, with her fine literary pedigree, Presbyterian upbringing, the theological underpinning of her more recent novels and her commitment to the United Church of Christ in the US, was an obvious “friend” with whom to linger — though, sadly, her piece felt way too short.

I concur with Freeman’s assessment that Robinson’s novels Housekeeping, Gilead and Home have been crucial to a generation of writers and they have certainly had a profound influence on me.

Freeman’s profile of Robinson also alerted me, somewhat belatedly, to her 1998 essay collection, The Death of Adam, in which she dismantles misunderstandings about the teaching of the theologian John Calvin. I now impatiently await this and Robinson’s latest essay collection When I Was a Child I Read Books and plan to devour them as soon as they arrive.

Freeman’s interview with David Foster Wallace from 2006 was moving in the light of Foster Wallace’s suicide in 2008. His death came on the back of debilitating mental illness and a change of treatment protocol that was not working. The terror this failure provoked is described poignantly in a piece by his wife, Karen Green, published on the Guardian website in 2011.

Freeman aptly describes Foster Wallace’s novelistic tour de force Infinite Jest (1996) as “a sprawling masterpiece about the toxicity of contemporary America, a world in which it was not illness but addiction that had become the defining metaphor of daily life”.

Fiction lets us in

Freeman also quotes Foster Wallace as saying, “If fiction has any value, it’s that it lets us in. You and I can be pleasant to each other, but I will never know what you really think, and you will never know what I am thinking. I know nothing about what it’s like to be you. As far as I can tell, whether it is avant-garde or realistic, the basic engine of narrative art is how it punctures those membranes a little.”

Foster Wallace, you will surmise, is hugely missed.

It is many years since I first read The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro and it was good to be reminded of this haunting tale of a repressed butler who realises much too late how misguided his loyal service has been.

How to Read a Novelist also had me reminiscing about Never Let Me Go, Ishiguro’s disturbing novel in which children are bred with the sole purpose of becoming body part donors when they reach their 20s and 30s.

It’s a novel that strikes at the heart of what it means to be human and mortal. And, as Ishiguro says in his interview with Freeman, “What really matters if you know that this is going to happen to you? What are the things you hold on to, what are the things you want to set right? What do you regret? What are the consolations? And what is all the education and culture for if you are going to check out?”

It was also moving to read Freeman’s assessment of Dave Eggers’ A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. This book, he said, “built a moat of irony around the loss of his two parents to cancer in the space of three months, sealing out the memoir’s sanctities in the process”.

Since it was released in 2000, Eggers has released several other titles, set up a book publishing firm, opened a drop-in non-profit tutoring organisation with eight locations around America, started a literary book review and an oral history project and got involved in a fight to improve teachers’ pay. Staggering indeed!

Freeman includes a clutch of writers whose work was new to me but to whom I was pleased to be introduced. One is Pakistani-born writer Mohsin Hamid, who criticises John Updike’s novel Terrorist. The book fails, Hamid argues, “for the same reason that America as a project fails: that leap of empathy is just one step too far.”

How to Read a Novelist is based on a good idea well rendered. It’s redolent of the Paris Review interviews (which I read voraciously in my 20s) but seem to have lost sight of since then.

The book is as close as most of us will come to being a fly on the wall of the lives and minds of writers who’ve helped shape our global landscape. I loved it because it is full of wit and wisdom; a buoy in the face of life’s inevitable swats.

PS: Freeman did score another interview with Updike and it went swimmingly.

Recent Comments