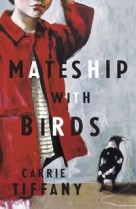

There’s no mystery as to why this delightfully easy-to-read novel is gaining plaudits. In Mateship with Birds Carrie Tiffany writes effortlessly and intriguingly about the natural world, rural life and desire. It’s a winning combination.

Set in the 1950s, on the outskirts of the Victorian country town Cohuna, this quirky novel serves up a scraggly clutch of houses, a motley crew of humans and a sprawl of farmland packed with fecund life.

Harry’s a dairy farmer whose young wife left him some years before for the President of the Bird Watching club. Harry’s neighbour, Betty, is a single mum who works at the local nursing home. She’s bringing up her two children, Michael and Little Hazel, in an easy-going fashion. Mr Mues, as his name suggests, is the creepy-crawly neighbour — a retired slaughterman — whose strange predilections eventually come to light.

Nature ripples around these humans and keeps them close to the cycles of death and birth.

It’s a pulsating world in which a great deal of looking and longing and lasciviousness is going on.

Little Hazel uses her binoculars to check on Foot Foot (a heifer Harry brought over for her to nurse because its front legs were twisted during a traumatic birth). Michael uses his binoculars to look down his girlfriend Dora’s blouse. Betty uses her children’s binoculars to scan the paddock. Harry uses his binoculars to check the cows, the kookaburras and the house next door to make sure that Betty, the children and the property are all fine.

Harry writes free verse about the kookaburra family he watches. His scribbling reveals his sense that the bond between these birds forms more organically, and their “mateship” flows more seamlessly, than it does for the people on the ground.

Each day Michael helps Harry with the milking and it’s clear Harry has cast himself in a fatherly role. He’s anxious for Michael to understand puberty and the mechanics and rapprochements of sex.

Some of this Harry explains quite candidly and reasonably eloquently in person using plants and textures in nature to illustrate his points. He also starts penning Michael letters because he finds that “some intimate topics are better tackled in the evening with a cup of Milo, a sharpened pencil and several sheets of Basildon Bond”.

These letters are quaintly formal rather than salacious. However, that Harry hasn’t told Betty beforehand that he is writing to her son about sex causes unnecessary concern.

I loved Tiffany’s alluring way with words and felt the whole book was a seductive adventure in language.

Here are three titbits:

- Sip, Harry’s dog, is useless with cows: “Her whole existence, every sinewy fibre of her, is tuned to the feel of Harry’s hand across the smooth cockpit of her skull.”

- Harry’s cows are characters. Babs “snorts pollard through her nostrils” and Licker and Big Joyce end up “jostling for the place in the line”.

- After school as Michael heads out across Foot Foot’s paddock towards Harry’s place and has “the sensation that he’s walking back in to himself. That … he’s moved through the day [at school] without ever putting his weight down. Here … there’s a rhythm to it. A way of placing your feet so they are receptive to the ground beneath.”

Tiffany is an agricultural journalist and I think this helps her to pin down the detail needed to build a convincing story. I’m now looking forward to reading her first book, Everyman’s Rules for Scientific Living, to see if she offers the same sorts of particularities there.

Lists are a Tiffany specialty:

- The items on the shelf in Harry’s dairy include: Provet, Vaginitis Powder, Killaweed, Sykes’ Bag Balm that “keeps teats as soft as silk”.

- Betty’s lists of Michael’s and Hazel’s illnesses include: Scratch from goanna, carbuncles, boils, and chilblains, Measles, pecked by gander and wandering off.

A variety of birds appear in the book, including kookaburras (aka Woop Woop Pigeon), magpies, butcherbirds, wagtails, lemon-crested parrots and crimson rosellas.

It is also explained that kookaburras have an unusual family structure. Groups of adult males and females live in celibacy with one central couple and assist them in hunting and raising their young.

The title Mateship with Birds comes from a book by a naturalist and bird lover, Alex Chisolm. His book about Australian birds was published in 1922 and has been republished recently by Scribe.

Mateship with Birds is a strong contender for a number of major literary awards, including the Miles Franklin, the Stella Prize and the Women’s Prize for Fiction, and I think you should read it.

Trust me: It’s an exhilarating flight.

I’m really pleased Carrie has won the Stella – I’ve followed her – mostly as a short story writer, for a while and I think she hasn’t gotten the notice she deserves, partly because of her subject matter, and partly because of the apparent simplicity of her writing which doesn’t try to bling at you, but manages to be exactly right. And she shared some of her prize money with the other shortlistees. What a woman!