What orients us historically if we don’t know our forebears during our childhood? Is our sense of family contained in houses or other environments? How tenuous are the links between parents and children? What haunts us from the past and why?

Lisa Gorton’s new novel, The Life of Houses, provokes this kind of questioning and probes how places speak to us. As Gorton says, ‘I wanted to realise in writing how, when we live in a familiar place, we seem to be moving about in structures of feeling: memories, worries and desires.’

What are we talking about?

The Life of Houses is the new novel by acclaimed Australian poet, Lisa Gorton, whose first book of poetry, Press Release, won the Victorian Premier’s Award for Poetry and whose second collection, Hotel Hyperion, was awarded the Philip Hodgins Memorial Medal. She has also written a novel for young adults called Cloudland.

Elevator pitch …

This is a mother-daughter story with an edge. When Anna’s 15-year-old daughter Kit lands at her grandparents’ house the narrative spins in several directions. One thread gives Kit glimpses of what her mother was like when she lived there. Another shows how the house and her grandparents are fading and how time can seem to simultaneously pass quickly and stand still.

‘If the atmosphere of the house was thick with feeling it was not their feeling for her — not for each other, either. In the house none of them could look at her without seeing the mother who was not there.’

The buzz …

Giramondo’s writers are always writers to watch — and the reviews of The Life of Houses so far have been favourable. Giramondo’s publicity compares Gorton’s style to that of Henry James — which indicates her work is worth a closer look.

The talent …

Gorton is an award-winning poet (see above) who studied poetry at the University of Melbourne under Chris Wallace-Crabbe. She also studied at Oxford University as a Rhodes scholar and completed a Masters in Renaissance literature and a doctorate on the poet John Donne — which won her the John Donne Society Award. She visited Ireland as the inaugural winner of The Vincent Buckley Poetry Prize and is the granddaughter of former Australian Prime Minister John Gorton.

In a nutshell …

Anna is a Melbourne gallery director who has had little to do with her parents since she left for art school two decades before. Her 15-year-old daughter Kit has only met her mother’s parents once when she was a toddler but doesn’t recall much about it. Recently separated from Kit’s father, Anna seeks space to pursue her affair with her lover, Peter. She sends Kit to stay with her ageing parents and her sister, Treen, who is their carer. At the family home, in a coastal town in south-eastern Victoria, Kit sleeps in her mother’s old room. As Kit explores the house and the town she encounters decaying architecture, ailing grandparents, curious townsfolk, ghostly rumours and stifling sadness.

It’s great that …

The book feels like a rambling house where rooms lead into other rooms — each space entered holding a trace of haunting. I didn’t find it a comfortable book at any stage, which I (mostly) came to see as a strength (by my second pass through). I also appreciate how the narrative swaps focus — alternating between mother and daughter — offering insights into their thoughts about each other and their thorny relationship.

It’s a shame that …

While there is some lovely writing in The Life of Houses, I found some passages too mannered. Certain phrases, metaphors and repetitions rankled and further alienated me from characters whose prickliness and strained relationships already made them a challenge to relate to. Some examples include: ‘Seagulls … tilting their eyes at each other like businessmen waiting for their morning coffee.’ ‘Kit was conscious of her grandmother … [and her grandfather reminded Kit of] one of the hand-drawn illustrations in Vogue, decorative calligraphy and watercolour, consciously obsolete.’ ‘Even here, in this room of muted good taste, they met intensely: his disapproval made them dramatic to themselves.’

Quote to mull …

‘Kit imagined her grandmother — lighter, a ghost of thought — stepping from room to room through the sleeping house, opening trunks and cabinets, wardrobes and sideboards, lifting each fact — spoons, forks, knives, books in their shelves, clocks, chairs and beds, curios and mementoes — out of a smell of damp, infestations of silverfish and moths, setting it in the unshadowed light of the page. In one folder Kit came upon the family tree, her name and birth-date handwritten in blue ink on the browning parchment. In this, she seemed to meet some other existence. Till now, family had taken meaning from the rooms of her parents’ house: their bedrooms and their meals together, their places on the sofa. Now she saw on the typed sheet lineage and years: family as a mechanism working its way through names. Her birth-date had a hyphen after it — she saw herself not exactly from the outside but from the long perspective of History. The feeling was so new that she felt startled and almost guilty when Treen knocked and put her head around the door.’

You’ll like it if …

… you liked Feather Man by Rhyll McMaster — another novel that broaches uncomfortable territory and tensions and that was also written by an award-winning Australian poet. Both narratives reference the visual arts and use poetically infused prose.

Why read it? …

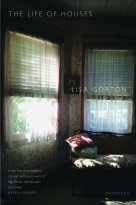

The Life of Houses examines the spaces that people visit, create and inhabit and how they reflect or affect the way they feel. It’s about the spaces that arise between people — how intimacy is gained and lost. It’s also about the push and pull of desire and obligation and how complex this tug-of-war can be. It should make you think. And you will have the wonderful cover — with its photo by Martin Cosby and design by Harry Williamson — to gaze at while you do so.

Recent Comments