Edith Campbell Berry is a fascinating protagonist and the Edith trilogy, of which Cold Light is the last, is a tour de force.

The trilogy took 25 years to write and the sweep of history this last volume of the work encompasses (1950 to the Whitlam era) is staggering.

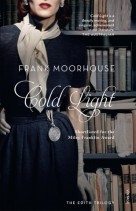

Like the other Edith volumes — Grand Days (1993) and Dark Palace (2000) — this latest offering from Frank Moorhouse — one of Australia’s truly great storytellers — is also meticulously researched.

The Edith trilogy has been compared in scope to Henry Handel Richardson’s The Fortunes of Richard Mahoney — one of our nation’s classics and most internationally lauded literary achievements.

The trilogy charts in intriguing and exacting detail the evolution of a 20th century Australian woman, the arc of politics and the changing mores of a world beset by idealism and despair brought on through war, nuclear cataclysm and failed attempts at peace-building.

In Cold Light, Edith, who has previously worked for the (now-defunct) League of Nations, has ambitions to be Australia’s first female ambassador. The ’50s, however, prove to be a tough time for women to climb the greasy pole of diplomatic service.

Instead, Edith gets caught up in what she considers the less lofty work of planning Canberra. Her vision is to create a city that is like no other and she proves pivotal to ensuring Lake Burley Griffin takes pride of place in this city — a city made out of paddocks, as Moorhouse points out.

It’s not easy for a woman with European sensibilities like Edith to settle down inCanberra. She moves there with her second husband, Ambrose, who has been posted to the city by the British High Commission.

In keeping with their Bloomsburyapproach to life, Ambrose continues to cross-dress when they are at home together sans company. Edith ponders what she calls “the split in his nature”, asking herself if his integrity lies in his management of his duality.

Their “etiquette of distrust” — not something Christian readers would admire — is reflected on years after she and Ambrose have divorced.

“She had known he had spied … and could not tell her. And, of course, she knew from very early in their relationship that he led a double life within his sexuality. He and she had discovered that the biblical betrayals of adultery could be turned in to erotic intimacy by candour.”

Conventional manliness

The split with Ambrose is precipitated by meeting (and later marrying) a man called Richardwho is more conventional and manly — and, also unlike Ambrose, he is not someone whose proclivities Edith must keep secret.

Marrying Richardalso offers Edith the opportunity to become a step-mother to his two sons but this yields less satisfaction than she’d hoped for at first. The marriage loses heat but does help smooth the way to her becoming a public liaison officer with the Australian Atomic Energy Commission.

Much of the tension in Edith’s early years in Canberrarevolves around the fact that her brother Frederick and his girlfriend Janice are Communists.

It’s risky for Edith to relate to them but she does — and there are some dramatic and clever scenes at meetings, during the Menzies’ government’s attempts to outlaw the Communist Party and flowing out of Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin in the “secret speech” to the Soviet Party Congress.

Fictional and historical characters — political, literary, feminist and scientific — appear as cameos or protagonists and the Who’s Who listing runs to six-pages at the end of Cold Light. The number of characters rivals Winifred Holtby’s Yorkshire-based South Riding but is, mercifully, not confusing.

Many of the sentiments and figures in Cold Light will be recognisable to Australian readers (Holt, Whitlam, Evatt and Hughes to name just a few) and this makes the work a prime candidate for future HSC and university reading lists.

As David Marr said in The Monthly, “Moorhouse has taken us on a strange voyage through the psyche of Australia. We’ve laughed. We’ve cried. We’ve had our differences. After all these years and pages we know ourselves and our place in the world better. It’s no small thing.”

Indeed, this teeming fictional stew includes history, sociology, psychology and diplomacy richly blended and good-naturedly examined.

Here’s a titbit from Edith about the latter: “Diplomacy was distrust within civilised urbanity — hearty laughter, charming conviviality and stiff face. It was like a masked ball, but it served a purpose and made good things happen.”

An imaginary world

As she grows older, Edith asks herself whether she has always taken on involvement in questions for which humans had found no satisfactory answers: world mediation, disarmament, nuclear weaponry and the dangers lurking within peaceful nuclear power.

“She saw that both Frederick and she had not lived so much in this world as in some vastly improved version of the world — an imaginary world, which they would fashion and to which the rest of the world would one day move.”

Born in Jasper’s Brush to rationalist parents, Edith sought over many decades to change society. As she ages, the fire in her belly calms and the number of drinks she needs to restore inner balance increases. While she’s still up for sexual and work adventures she’s also asking hardquestions about whether the second half of her life devoted to the peaceful use of uranium has been another lost cause.

“Was the world too hardto manage sensibly? Did it always move on towards its own destruction?”

Edith’s questions set me on to pondering others:

Is the fruit of diplomacy (or being part of a diplomatic milieu) most often disappointment — based, as diplomacy is, on grand vision but so often confounded by human frailty, hunger for power and pettiness?

Do the sands of time cover most people’s achievements in the end, blur their tracks?

How redolent is Edith of the flesh and blood woman from which (at least parts of Edith’s marvellous complexity) was drawn?

The “answer” to my last question is poignant.

While creating Edith, Moorhouse chased down every wordwritten by Canadian and formerLeague of Nationsemployee, Mary McGeachy.

He then visited her when she was 90 to hear her life story.

Instead, McGeachy asked him to recount her life story because she had forgotten it!

I doubt I will ever forget Edith Campbell Berry — and, if I do, I will have the trilogy in pride of place to help remind me. With all her fascinations, foibles and furbelows she is a true wonder of the fictional world.

Moorhouse, I salute you!

Recent Comments