Finally, I give you EOFY (Part 2). This is fiction I’ve read in 2016 but not blogged about (until now). There’s an array of titles here for you to seek out in the New Year. Enjoy! You can also read EOFY (Part 1) here.

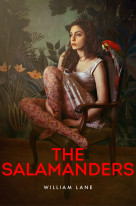

The Salamanders by William Lane

Peregrine is a self-absorbed artist who shares a summer holiday with his blended family featuring ex-wives, numerous offspring (including an adopted daughter who is a Koori) and several other hangers on. It’s a liberating but precarious time for the children, and the two most affected are Arthur and Rosie, who carry their quandaries into later life. Rosie has mostly lived in England but visits Arthur in his hut on the Hawkesbury River, after which they head to inland Australia on an odyssey that unearths origins.

Lane vividly describes the Hawkesbury and other parts of our ancient land. He also shows us how parents can visit pain upon their children, and the tidal pull that place and art can assert on our psyches and souls. Read this beautifully strange book slowly and ponder its depths.

Here’s a quote:

I’m on the road to the original state that exists before reading. Everything is more lucid there, don’t you think? Words are smoke. All symbols clutter and veil reality by substituting themselves as reality. There’s really no need for it. Can you remember the time before reading, and wasn’t it brighter, more distinct and more animate? Anyway, everything I ever read only seemed to confirm what I best knew first. Harriet reads everything for me now. Remember Harriet, my agent? She was here a while ago, but I think she’s gone now.’

Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett

I’ve already blogged about ‘Control Knobs’, which is one of the 20 stories in this unique debut collection (so you can read that post here). The narrator in Pond is a semi-reclusive woman and we never learn her name or the name of the place in which she lives. We are, however, given wide-ranging access to her thoughts. At one point she says, ‘I don’t want to be in the business of turning things into other things … making the world smaller’. If this is also Bennett’s intent in her fiction, it works, insofar immersing myself in her character’s thoughts and day-to-day activities, my world seemed to expand a little as well. Two of the shorter stories, ‘To a God Unknown’ and ‘Two Weeks Since’, were among a handful of favourites.

Here’s a quote from ‘Two Weeks Since’:

White. A white horse standing, looks this way, then turns. Gave birth in the meantime. Blood fresh all the way down hind legs, cord hangs. A black foal slides about nearby, tiny forehead opening a warm pale star. Heart lengthens: cord swings.

Little Failure by Garry Shteyngart

It took me a while to warm to this funny, sad, raw, and rollicking memoir. But once I did, it just got better and better. Shteyngart’s family migrated to America in 1979 and the young Garry entered a world of shame and pain. We follow the ‘little failure’(or failurchka as his mother calls him) as he attends Hebrew School; stands out because of his Soviet upbringing; attempts to assimilate into Amercian society through the use of humour, self-deprecation and some pretty inelegant posturing; and as he journeys to Russia (which he describes with excruciating insight and candour). We also learn how Shteyngart finds his voice as a writer, and gradually builds his sense of belonging. You’ll laugh, cry and enjoy the work of a master memoirist as he straddles contradictory worlds and uses his wit and wisdom to both survive and describe them.

Here’s a quote:

‘Perhaps the greatest unanswered question I have toward the entire Land of the Soviets is this: Who did the sewing? In a country recovering from the greatest war humanity has ever known, with twenty-six million in their graves (my grandfather Isaac included), who took the time out of a starving, snowy day to carefully hand sew the tiny photo of a smiling four-year-old, my mother, into the “criminal” case file of a man—a boy, really, by today’s standards—who had watched his family die just half a decade ago, who had fought the enemy back across the border, and who had subsequently been imprisoned for writing poetry and admiring a German tank?’

When It Rains: A Memoir by Maggie Mackellar

In two short years Maggie Mackellar’s life went from positive to hellish. Her beloved husband and father to her five-year-old daughter and an unborn son, committed suicide. Her mother, who has been a great support to her, was diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer and died suddenly.

Mackellar tries to continue with her academic career despite being a newly single mother who is also debilitated by grief. She survives for a year, then chucks it in, and returns with her children to the family farm in central western New South Wales.

The earthiness of the place and people, the regularity of the family’s routines, and the physicality of farm life all start to work their magic. The animals and the weather provide challenges (of course!) but gradually—tentatively—Maggie feels she might be healing. Her children also start to settle and find their feet.

This engaging memoir doesn’t sugar coat grief or underplay how hard it can be to build a new life.

Here’s a quote:

I wonder how much of our memory is held in our heads and how much is in our blood, or muscle or bone. Put the sheep into a new paddock, a paddock they haven’t been in for a long time, and they remember, collectively, where the water trough is. … These moments of remembering are all straightforward, but what I’m thinking about is the memory unconsciously within us. When you kill a rooster, its head, violently separate, is still. But its body resists death, flaps a protest. It would crow if it still had a mouth. Instead, it struts, twirls, staggers, falls. It fights and remembers life with every twitch, finds the ground, is drained of blood and only then gives in to death.

Is this me? Seeking the trace of him, the smell of life he may have left behind. My muscles ask no question, they just hold his shape; hold it until he runs out like blood.

Commonwealth by Ann Patchett

I’m partial to narratives that feature parties and Commonwealth is bookended by two. The first is in LA in the 1960s and the second is 50-odd years later in Washington DC. This initial party is pivotal. Fix and Beverley Keating have invited family and police from the LAPD (where Fix works) to celebrate their second daughter Franny’s christening.

Upstairs, Beverley is drawn to kiss the deputy DA, Bert Cousins—and thus begins the blending of two American families, with six children between them.

As we follow the Keating and Cousins children into adulthood, we learn fragments of their histories. By the end of the second party, we know that one has died, another will enter a Swiss monastery and one is a novelist who has turned the family story into a novel that’s been made into a film the family hates.

Commonwealth has a large cast so it’s sometimes difficult to remember who is who, and details can sometimes seem a little too sketchy.

Despite this, Patchett’s 10th novel is intriguing enough to follow the siblings to the end. It’s also clever in how it gets readers to ponder whether family stories are ours alone, and if we should feel at liberty to mine them without the permission of other family members for fictional and/or filmic use.

Here’s a quote:

He liked the feeling he didn’t have a name for when he saw Fode on the front steps waiting for him late at night with a beer. He would leave them eventually, but until then he would bring home cold sesame noodles from Chinatown, he would fold up his blankets every morning and put them behind the couch, he would find reasons to stay out late several nights a week in order to ensure their privacy, and when he came home very late, he would turn his key in the lock so quietly that he would never wake them.

‘Where were you last night?’ Jeanette would ask, and Albie would think, You missed me.

Bright, Precious Days by Jay McInerney

Although Bright, Precious Days is the third novel in McInerney’s trilogy, which includes Brightness Falls (1992) and The Good Life (2006), it’s the only one I’ve read. I don’t think this matters, as it’s easy enough to pick up the story of Corrine and Russell Calloway, now in their 50s, and still living in New York.

The couple have two children, thanks to eggs donated by Corinne’s younger sister Hilary. Russell has bought a publishing company with the backing of some investment bankers. Corrine is writing a screenplay and resumes her affair with Luke McGavock, who is refusing to grant his young new wife her wish to have a baby.

Luke is not the only character who seems vain, self-serving and superficial. As another says about the 9/11 attacks, ‘We were all going to change our lives, and in the end we’re the same shallow, grasping hedonists we used to be.’

Well, yes.

Perhaps McInerney’s finest achievement is that he gets us to care (if only fleetingly) for these flawed and entitled people, and their (at times) fatuous take on life. Another is how well he describes a changing New York, and shows us why some of its citizens, like Russell (who are rapidly being priced out of its property market), remain deeply attached to living in it.

Here’s a quote:

In a more general sense, Russell objected to the cult of personality, to the fake idea of authenticity, to the notion that the intensity of the life, somehow certified the work, all the holy drunk/genius junkie bullshit that equated excess with wisdom, cirrhosis with genius.

His dead best friend, [Jeff] the genius junkie, was posthumously developing a cult all his own. Sales of his books were steadily climbing. It seemed like such a damn waste. Sometimes, still, it would hit Russell hard, how much he missed him. How angry he was at him still for not being around. No one had ever completely replaced him.

The Burgess Boys by Elizabeth Strout

Like so many brothers the world over, Jim and Bob Burgess have a way of relating that’s habitual if not totally comfortable. Jim is a corporate lawyer of some notoriety and Bob is a legal aid attorney. Both live in New York City, having moved there in their early adulthood from their hometown of Shirley Falls in Maine. Jim big-notes himself and belittles Bob. Bob takes it on the chin because he admires his big brother. Both Burgess boys admit they’re less fond of their sister Susan (Bob’s twin), who still lives in Shirley Falls, and whose divorce has left her with scars.

Two events lie at the heart of this compelling narrative. The first is the freak accident that killed the Burgess children’s father when they were young. The second is when Susan’s troubled teenage son Zach commits an act that deeply offends the local Somali community, and is deemed to be a hate crime.

When Jim and Bob return to Shirley Falls to help organise their nephew’s defence it unearths memories and tensions that will have a profound effect on the brothers and all their relationships.

Strout showed us through her Pulitzer prize-winning book Olive Kitterage that she has an uncanny knack for illuminating human nature. It is evident again here. She also probes several pressing issues relating to racism, immigration and multiculturalism that the US and other developed nations are continuing to struggle with in these times.

Here’s a quote:

There were Saturday evenings, like this one, when Pam, with her congenial husband, stepped off an elevator into the foyer of an apartment where globes of yellow light and fabulous shadows played throughout the rooms beyond, when leaning to kiss the cheeks of people she barely knew … Pam would think, as she did now, This is what I wanted.

What she meant, exactly, she could not have said. It was simply a truth that had clamped down on her with gentle snugness, and gone, gone, gone were those needling thoughts that she was living the wrong life. She was calm with a completeness that seemed almost transcendent, this moment that spread before her with the assuredness of itself. Certainly nothing in her past—the long, bike rides on the farm roads of her childhood, the hours spent in the cosy library, the creaking floored dormitory in Orono, the tiny home of the Burgess family, not even the excitement of the Shirley Falls that had seemed the start of adult life, or the apartment she had shared with Bob in Greenwich Village, thought she had like that apartment very much, the noise on the streets at all hours, the comedy clubs and jazz clubs they had gone to—nothing had indicated to her that she would want this and get this, right here, this particular kind of loveliness so gracefully and astonishingly taken for granted by the people who spoke to her with nodding heads.

Recent Comments