Nobody does melancholic reverie quite like the American author, poet, singer and songwriter Patti Smith. Her autobiography, M Train, published late last year, has this elegiac and quietly celebratory quality in spades.

Imagine life passing like a train trip. Snatches, fragments, impressions caught along the way and recorded, then simmered and stirred into poetic prose. This is Smith in M Train. She brings her passion and precision to her alchemical assignation and reveals the startling, beautiful and transient connections from which our fleeting time on earth is made.

M Train is not a companion piece to Just Kids, her award-winning 2010 autobiography that focused on Smith’s growing skill and conviction as a poet and singer in New York city and her relationship with the artist and photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.

It is Patti Smith growing old. At 69 (and even at 66 when she was writing M Train) she has a lot of life and artistic achievement behind her; a jumble of habits and interests that fill her present; and times ahead that will contain (we hope for her sake and ours) much more of the same.

At 69 there’s been a lot of loss—including the deaths of her husband Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith and her brother Todd in 1994, very close together.

‘My brother stayed with me through the days that followed [Fred’s death]. He promised the children he would be there for them always and would return after the holidays. But exactly a month later he had a massive stroke while wrapping Christmas presents for his daughter. The sudden death of Todd, so soon after Fred’s passing, seemed unbearable. The shock left me numb. I spent hours sitting in Fred’s favorite chair, dreading my own imagination. I rose and performed small tasks with the mute concentration of one imprisoned in ice.’

Smith loses objects too—notebooks, cameras, coats and napkins scrawled with her ideas—and this disconcerts her because many of the objects contained talismanic or practical significance (and, at times, both). She riffs on returning these lost objects to their true origins, ‘a crucifix to its living tree or rubies to their home in the Indian Ocean. The genesis of my coat, made from fine wool, spinning backwards through the looms, onto the belly of a lamb, a black sheep a bit apart from the flock, grazing on the side of a hill. A lamb opening its eyes to the clouds that resemble for a moment the woolly backs of his own kind.’

Black coffee and writing in bed

Smith is a woman of routine who loves her black coffee and who mourns when her beloved café near her house in New York is closing down. She has written there each day, she says: ‘I loved my coat and the café and my morning routine. It was the clearest and simplest expression of my solitary identity.’

In the café, she scribbles in her notebook or on serviettes or other scraps of paper—dwelling on ideas and memories and ruminating on her changing moods.

‘I sit before Zak’s peerless coffee. Overhead the fans spin, feigning the four directions of a traversing weather vane. High winds, cold rain, or the threat of rain; a looming continuum of calamitous skies that subtly permeate my entire being. Without noticing, I slip into a light yet lingering malaise. Not a depression, more like a fascination for melancholia, which I turn in my hand as it if were a small planet, streaked in shadow, impossibly blue.’

Smith also likes to write in bed (me too!) and her depiction of her workspace and writer’s accoutrement made me smile.

‘I have a fine desk but I prefer to work from my bed, as if I’m a convalescent in a Robert Louis Stevenson poem … Occasionally I write directly into my small laptop, sheepishly glancing over to the shelf where my typewriter with its antiquated ribbon sits next to an obsolete Brother word processor. A nagging allegiance prevents me from scrapping either of them. Then there are the scores of notebooks, their contents calling—confession, revelation, endless variations of the same paragraph—and piles of napkins scrawled with incomprehensible rants. Dried-out ink bottles, encrusted nibs, cartridges for pens long gone, mechanical pencils emptied of lead. Writer’s debris.’

Her eloquence about writing and language can be breathtaking. ‘Leaves as vowels, whispers of words like a breath of net. Leaves are vowels. I sweep them up hoping to find the combinations I am looking for. The language of the lesser gods.’

At the beginning of M Train, Smith dreams about a cowboy who says: ‘It’s not so easy writing about nothing.’ She is haunted by the cowboy’s idea and decides to pursue it. M Train is the result—but it is not about nothing. It is about many things, small and large, such as grief, love, ageing, artistic inspiration and a ramshackle bolthole she buys in the Far Rockaways and that is damaged soon after by Hurricane Sandy.

Of her Rockaway purchase she muses, ‘Anxious for some permanency, I guess I needed to be reminded how temporal permanency is.’

Paying homage to inspirational artists

In M Train Smith pays homage to the authors and artists who have guided her artistic journey and to whom she is deeply grateful. She reveals the touchstones that have helped shape her communion with these creators. She describes how she’s traveled the world like a religious pilgrim to get these relics or to give them to others; relics glowing with meaning and gratitude.

An early part of the book is set in the 1980s when she and her (then) new husband the guitarist Fred “Sonic” Smith visit the abandoned penitentiary in French Guiana where the author Jean Genet had been imprisoned. Smith digs up stones that she imagines the prisoners and guards have pushed into the ground with their feet and boots. She carries the stones away in a matchbox wrapped in Fred’s handkerchief—‘the first step toward placing them in the hands of Genet’.

She describes trips to Berlin, London, Tokyo, Mexico City and Tangiers to give speeches, visit landmarks and to take Polaroids of objects associated with authors and with others from whom she’s gained sustenance. These include Sylvia Plath’s grave, Frida Kahlo’s house and Kurosawa’s memorial. Reproductions of some of these black-and-white Polaroids—including Virginia Woolf’s walking stick, Frida Kahlo’s crutches and Tolstoy’s bear—are scattered throughout M Train’s pages.

‘I have stacks of Polaroids, each marking my own, that I sometimes spread out like tarots or baseball cards of an imagined celestial team,’ writes Smith. ‘There is now one of Sylvia in spring. It is very nice, but lacking the shimmering quality of the lost ones. Nothing can be truly replicated. Not a love, not a jewel, not a single line.’

I was not surprised to learn that Smith has immersed herself in the work of authors like Roberto Bolaño, W.G. Sebald, Albert Camus, Vladimir Nabokov and Paul Bowles as they are all outstanding writers. I was surprised to learn that she is a crime-show fan who watches Morse, Lewis, Wycliffe, Frost, Cracker and other series to the point of obsession. (Although, to be honest, I was relieved to learn that, as well as being brilliant, she is also ‘normal’.)

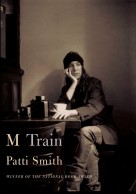

While M Train contains scant mention of the music making or performing that has contributed so much to her notoriety, it does indicate that her artistic vision and vocation remains a driving force. Reviewers have remarked on the sadness and solitude in Smith’s face as she appears on the cover of M Train—and there is no doubt that writing and ageing can be a lonely business. Smith herself says that M Train is ‘as close to knowing what I’m like as anything’.

Savouring the subdued palette

I meant to write about M Train soon after I devoured my review copy over two days. Unfortunately, life got in the way. I was happy to find it is the kind of book that can benefit from lying fallow. Over the last few weeks, I’ve enjoyed dipping in and out of it again. This week I’m savouring it more leisurely; reading it (from cover-to-cover) a second time.

I love the fragmentary nature of M Train and its subdued palette. What it reminds me of most are those dark nights spent watching snatches of film or random slides with my family. I was too young to always grasp the meaning of this footage—even though it mainly consisted of home movies and snaps of my mother on a world trip she took before she married my father. But the hum of the projector and the sharp light that struck through the darkness that surrounded us gave me a sense of something deeper. It may have been the possibility of adventure, or a longing for narrative or a flickering understanding that there was more to life than meets the eye, I can’t say.

I know I can’t go back to that suburban lounge room with the people who raised and grew around me like a glade of gum trees—and yet I’d like to (at least for a little while). And it is this kind of yearning that Smith expresses so well. ‘We want things we cannot have. We seek to reclaim a certain moment, sound, sensation. I want to hear my mother’s voice. I want to see my children as children. Hands small, feet swift. Everything changes. Boy grown, father dead, daughter taller than me, weeping from a bad dream. Please stay forever, I say to the things I know. Don’t go. Don’t grow.’

The M Train on the New York subway flashes through 14 ‘stations’. And, like the transitory visions seen from the train’s window, our swift passage through life and the impermanence of the people and the objects around us makes remembering moments—radiant and beneficent—significant.

As Smith says, ‘You think some things will go on forever—your children will always be small, your husband will always be alive—but time passes … Memory is our most fertile souvenir.’

Recent Comments