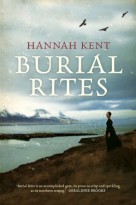

Hannah Kent is a rising star in Australia’s literary firmament and the release of Burial Rites last month in Australia, and in the next few months in Britain and the US, is the major reason for her ascent.

Literary critic Stephen Romei said Kent’s book was “the most talked about Australian debut novel in years”.

For me its tidal pull arose from two sure sources: Kent’s nuanced portrayal of an Icelandic woman, Agnes Magnúsdóttir, convicted of murder in the 1830s; and her soulful evocation of Iceland’s harsh and haunting landscape.

It’s a heady brew.

Kent is the Deputy Editor of the Melbourne-based literary journal Kill Your Darlings. In Volume 13 of the journal she has detailed the nerve-wracking process of bringing Agnes’ story to life.

Writing the novel, she said, was like “being abducted from my bed by a clown, thrust into a circus arena with a wicker chair, and told to tame a pissed-off lion in front of an expectant crowd”.

Despite eventually disciplining herself to write 1,000 words a day and producing a tower of drafts over half a metre high, Kent said, “The fear of not knowing where I was headed and the best way to get there never abated.”

Her persistence in facing these fears paid off. She secured a two-book deal worth more than $1 million and translation rights for Burial Rites have been sold to 15 countries.

Icelandic obsession

It was a trip Kent made to Iceland at 17 as a Rotary Exchange student that planted the seed she nurtured into her well-received first novel. Kent felt lonely and isolated in Iceland — even though the landscape felt “like a homecoming” — but it was here she first heard about 34-year-old Agnes and her alleged part in the violent murders of Natan Ketilsson and Pétur Jonsson.

It took years of obsession, a PhD in Creative Writing and much painstaking research — including a return to Iceland to study the public records — to put flesh on Agnes’ bones and to understand the grim era and landscape in which she worked and lived.

The few facts Kent managed to glean about Agnes acted as grit to a pearl. Ultimately they drove her to fashion a character much more multi-faceted and ambiguous than the historical records portrayed.

In 2011, Burial Rites won the inaugural Writing Australia Unpublished Manuscript Award and this gave the draft novel its next significant lift.

The prize included a mentorship with renowned US-based Australian novelist Geraldine Brooks, who said Kent’s work was so accomplished her only significant input was to encourage her “to let more light and warmth into the northern chill”.

The result is a smoothly-told and convincing tale in which the dark shadows strike base notes rather than casting an airless pall.

Spurned love and desire

Agnes gets sent to the farm of the District Officer Jón Jónsson and works as a servant while awaiting her execution. Jónsson’s wife, Margrét, and two daughters, Steina and Lauga, are understandably wary of the interloper who sleeps alongside them in the communal living room (known in Iceland as the badstofa).

Their wariness dissolves slowly as Agnes contributes her skills and knowledge to benefit the family and wider community: calmly delivering a breech baby; recommending boiled moss to soothe Margrét’s cough; and working around the clock during harvest and slaughter.

As winter closes in, Agnes also reveals more of her life story to Tóti, the young assistant minister, sent to instil in her a desire for repentance and a return to Christian purity.

Inside the badstofa, the family listen in, as well, to Agnes’ tale. Their compassion is drawn forth as she talks without self-pity of a hard life with more than its fair share of pain.

Details relating to the stabbing and bludgeoning of the two men are also unveiled slowly and an intrigue of spurned love and hot-headed desire eventually comes to light.

Precise prose

Overall, there was an easy momentum to Burial Rites and a well-paced unfolding of story that carried me along without difficulty to the book’s inevitable conclusion.

I particularly enjoyed Kent’s precise prose and convincing depictions of the visceral. A knife in the guts, a debilitating cough, the bodily response Agnes has when she is told the news that her execution is imminent — such embodied moments had veracity due to fine-tuned description.

Kent also did well in evoking the Spartan isolation in which the rural people of Iceland lived and worked two centuries ago. It certainly reminded me of the fortitude and strength needed to survive in such a hard landscape.

As I read I placed sticky notes on pages so I could easily return to relish phrases that appealed.

Here are a few passages (all from Agnes’ point of view, as it happens) to tempt you to explore the book further:

- It was late in the day: the wet mouth of the afternoon was full on my face.

- At Hvammur, during the trial, they plucked at my words like birds. Dreadful birds, dressed in red with breasts of silver buttons, and cocked heads and sharp mouths, looking for guilt like berries on a bush.

- When I was her [Steina’s] age, I was working for my butter at Gudrunarstadir, helping with five children there — each as thin and faint as tidemarks — and cleaning and cooking, and serving until I thought I’d collapse.

- This is my life as it used to be: up to my elbows in the guts of things, working towards a kind of survival. The girls chatter and laugh as they stuff the bags with the bloody mix. I can forget who I am.

- Reverend, my mouth aches. My tongue feels so tired; it slumps in my mouth like a dead bird, all damp feathers, in between the stones of my mouth.

- The sea is different up around Vatnsnes. Sometimes the water in the fjord is like a looking glass. Something you want to run your tongue across. “As glazed as a dead man’s eye,” as Natan used to say.

Keeping it taut and real

Kent says that making Agnes’ story the subject of her PhD was one of the most uninformed and ridiculous decisions she had ever made.

“Un-practiced and unskilled in any form of novel-writing or biographical research, I publically committed myself to writing a full-length manuscript about a historical figure I knew nothing about, set in a country not my own, in a time I was utterly unfamiliar with. Some people kindly called it an ‘ambitious’ project. I think ‘indicative of a student who has no idea what she’s doing’ would have been more appropriate.”

Ambitious it may have been, but readers should be grateful that Kent plunged in and, despite her fears, learnt the secrets to making a good novel.

At 27, she has plenty of time to learn more! In writing her second book, I hope she keeps it equally taut and real.

Recent Comments